US airlines reported $4.9 billion in checked bag fees in 2018, up from $4.6 billion in 2017 according to data released by the Bureau of Transportation Statistics. That’s often taken to mean money they’re making on checked bags but it’s highly misleading.

| Airline | 2018 | 2017 |

| American | $1.22 billion | $1.17 billion |

| United | $889 million | $795 million |

| Delta | $788 million | $908 million |

| Spirit | $638 million | $493 million |

| Frontier | $366 million | $364 million |

| JetBlue | $321 million | $290 million |

| Alaska | $280 million | $210 million |

| Allegiant | $220 million | $193 million |

| Hawaiian | $85 million | $81 million |

| Southwest | $50 million | $46 million |

Delta and United traded places on this list and so did Alaska (including Virgin America) and Allegiant.

American’s leadership here isn’t surprising. They’re the largest US airline and their business is disproportionately domestic (where first bag fees are most common), and their international network is Latin-heavy carrying significant checked baggage. United’s business is disproportionately international.

It is interesting though to see the drop in bag fees at Delta, generally thought to be the best-performing US airline. They also derive the greatest portion of their revenue from fare upsells, which bundle checked bags. The most successful US airline appears to be moving away from baggage fees and unbundling, they’re also the carrier (after JetBlue) testing free inflight wifi.

Meanwhile United may be driving higher checked bag fees from passengers on basic economy fares who are not allowed to bring a carry on bag onto the aircraft. Notably it may be the lowest airfares, then, driving higher bag fees.

Here’s why ‘checked bag revenue’ is not ‘how much money they made on checked bags.’

- Ticket prices used to include bags, now they don’t and ticket prices have fallen. Airlines are earning less than they would have on airfare. Clearly some people pay more, but not everyone, there’s a lot of ‘moving money around’ going on here.

- Checked bag fees also cost airlines money delaying flights and leading to less efficient use of aircraft, since passengers try to bring all of their worldly possessions onto the aircraft.

- One of the big drivers of profit here is hidden and explains a lot — tax arbitrage. Airlines are saving the 7.5% excise tax on domestic airfare when they move money out of the fare and into fees.

Hate checked bag fees? It’s the tax code’s fault. And any politician who rails against these fees without mentioning the politician’s own role in the tax code isn’t being honest.

Last year a man checked a can of beer as luggage on a Qantas flight.

Are Airlines Really Taking in More Money When They Charge Checked Bag Fees?

Tickets used to come with checked bags. Now most domestic tickets include transportation with checked bags sold separately. Passengers checking bags aren’t suddenly willing to spend more for air travel than they were before.

Some passengers were willing to spend more than they were being charged of course, so targeting them with higher prices raises more revenue. However bag fees tend to fall heavily on the most price sensitive consumers (non-elite leisure travelers).

For many customers, willing to spend as much as before, fares just fall and the total trip cost remains the same. Indeed, airfares have been falling since checked bag fees were introduced over a decade ago.

Some of the checked bag fees represent revenue at the margin the airline wouldn’t have earned if they were still bundling bag fees in with fares, but certainly not most. The point is this isn’t all new revenue to the airlines. Indeed Southwest Airlines even thinks they make more money not charging checked baggage fees. (Their first two checked bags are free, but they still earned $50 million in additional bags and heavy bags.)

Checked Bag Fees Impose a Cost on Airlines

Checked bag fees push more bags into the cabin. More carry on bags slow down the boarding process. And slower boarding means less efficient use of aircraft and more delays, which can cost airlines nearly as much as they’re taking in in bag fees.

Gate checked bags add a few minutes to the boarding process — passengers try to find overhead space, then wind up going back to the front of the aircraft to gate check, plus 1-2 minutes to move gate-checked bags to the belly of the plane — and extra bags in overhead bins add a minute or two to deplaning.

Elite frequent flyers (frequently with aisle seats) board first to ensure they get bin space. Boarding forward cabin aisle seats first slows down boarding — those passengers get up to let middle and window seat passengers into their row and then have to sit back down while the rest of passengers are held up getting to their rows.

A few minutes here and there is a big deal to an airline, Southwest’s CEO claimed “It would cost us approximately 8 to 10 airplanes of flying per day if we were to add just a couple of minutes of block time to each flight in our schedule.”

That’s because you don’t just push your schedule later into the night, you have to schedule flights when passengers want to fly and at times they’re most

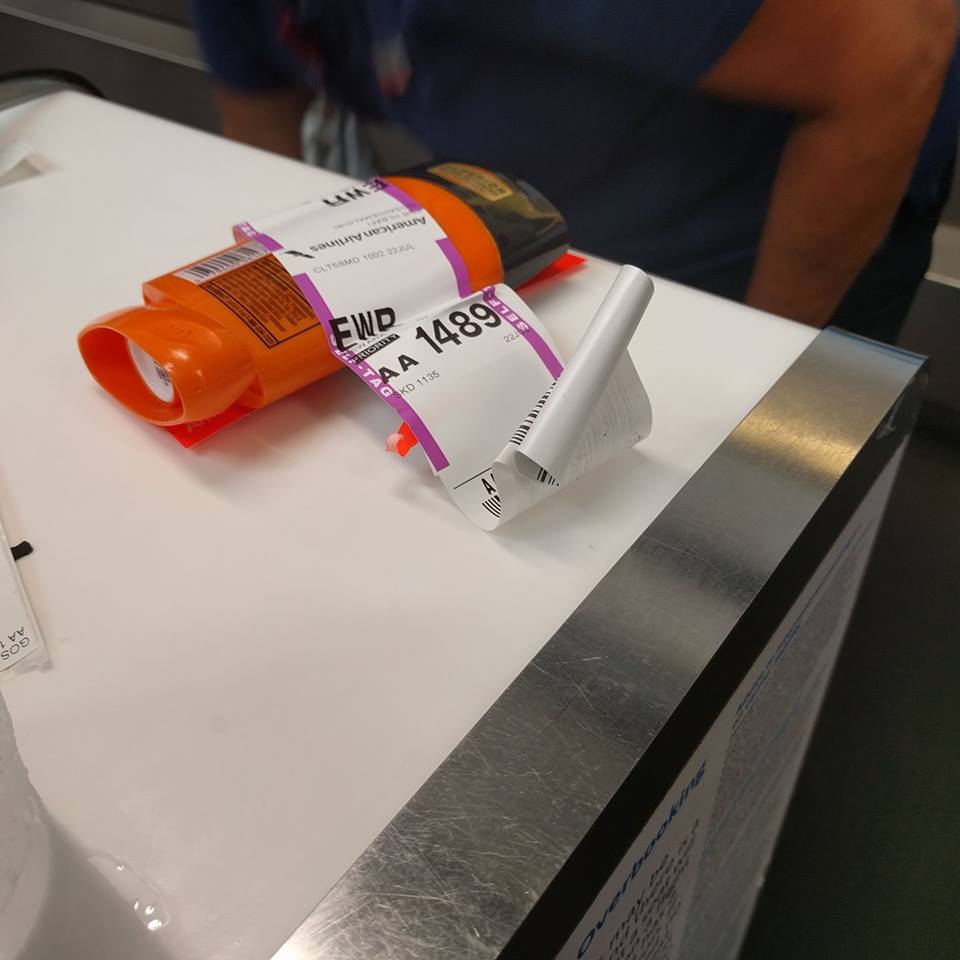

Blog reader Hemal G checked deoderant onto an American Airlines Charlotte – Newark flight because he wanted to use his free checked baggage allowance.

Checked Bag Fees are Tax Arbitrage

There’s an excise tax of 7.5% on domestic airline tickets. That tax doesn’t apply to fees. So by moving bag fees out of the base fare airlines pocket a huge tax savings.

If $4.9 billion would have otherwise been part of airfares (it wouldn’t have been, and some of the checked bag fees are from international flying which doesn’t incur the excise tax) that would mean $368 million in tax savings for US airlines in a single year. It’s reasonable to think the tax savings is half that, however.

Ultimately checked bag fees themselves aren’t the big business that simply summing up the charges from an accounting standpoint would have you believe.

Superb and insightful article. This type of journalism, combining news with genuine analysis to produce insight is very rare these days.

I’m not sure I understand your point about the 7.5% excise tax (US). US is passed on to the consumer. So where is the arbitrage opportunity for the carrier?

I feel like we just had this exact argument over frequent flyer mile sales to banks. I said it would be a gadfly question for an analyst to ask management why they don’t make money flying airplanes because analysts know it’s all a rebating mechanism for the core flying airplanes business. My point was that you can’t say they make all of their money selling points to banks because it is all part of the same business, without an FF program, they would find a way to be profitable with an alternative way of rebating. And you called it “fairly silly” to think they would be profitable without a FF program. Seems you are making the opposite argument here. Why isn’t it ok to say they make all of their money on bag fees, but it is ok to say they make all of their money selling miles?

Southwest’s checked bag revenue surprises me. First two bags are free. So that’s a lot of third and fourth bags.

1. Agree with @Colin Zw: If excise tax applied to ancillary fees, the tax would simply be passed along to the consumer. A checked bag would be, say $30 + Fed excise tax or $32.25 final charge to the customer. The airline still pockets $30.

2. Yes, the airlines really did make $4.9B from checked bags – that’s what they brought in. The question of their net profit from those fees is separate and I can’t imagine anyone assumes that represents their profit. Also separate is the question of what their bottom line would look like if bag fees weren’t charged.

> “The most successful US airline [Delta] appears to be moving away from baggage fees and unbundling”

Delta is not the the most successful US airline from a financial returns standpoint; Southwest is. They never succumbed to the total idiocy of “unbundling” and never added bag fees, and have kept the money train rolling in. Also interesting to note is that JetBlue resisted bag fees for a while, but since they’ve introduced them, their financial performance has been sliding.

And yes, Congress should wake up and apply transportation tax to the fees for the transportation of bags.

Delta also seems to have a higher percentage of credit card holders than other airlines, which reduces checked bag revenues, but greatly increases cobrand credit card revenues

@Colin Zw & @Ryan:

By moving checked bags out of the cost of the ticket it lowers the overall price of the ticket. So carriers that unbundle have a lower total price for the exact same revenue as carriers that bundle.

Good Article. My Question. How much of the merchant charge that the bank charges is paid to the co-branded airline/hotel/whatever credit card? Certainly the company must not only be selling miles/points to the bank but also receiving payments for co-branding on a continuing basis.